For taxable investors, it is not enough to get excellent long-term after-tax performance from an investment fund. Persistence – the ability to remain good to excellent through time — matters just as much. Why? The journey matters.

If the road is too rocky, investors will lose faith and feel compelled to fire a fund manager. That issue is then compounded by taxes. While tax-exempt investors can afford to “date” their funds, flitting from one to the other frictionlessly, taxable investors, in contrast, usually pay a heavy tax when they sell – what we call “divorce costs .” This erodes the chances of ever banking those excellent long-term returns.

Funds showing higher persistence – a smoother road, on the other hand – enable an investor to stay “married.”

Comparing two investment funds illustrates the point. Both provided essentially identical and excellent long-term after-tax returns. Both were in the exact same small-cap value category. One was difficult to stay married to. The other is much easier.

The first fund, Fund X1 was recently lauded, two weeks in a row, by Barron’s. The article highlighted an +11% return in 2022, impressive, given that US small-cap value stocks were down -15%. A week later, Fund X’s manager was profiled in a flattering interview. He had what Barron’s readers love to see in active managers: Concentrated high-conviction portfolios. “Get your hands dirty” fundamental research. A stock-picking methodology fawningly compared to Benjamin Graham, the “Father of Value Investing.”

Historical performance numbers also spoke to its long-term excellence. It had beaten over 90% of its peers over the last 10 years. Morningstar analysts assigned it a Silver rating.

This looked like a fund suitable for marriage.

Here’s the wrinkle.

Our clients pay taxes. Typically, 85% to 95% of their investment assets are taxable. Further, many of our clients are in the highest Federal marginal tax bracket. Further still, many happen to live in high-tax states, such as New York, California, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. The combined tax bill on short-term gains, for example, approaches 57% in some states. When the 2017 tax cuts sunset, that number could approach 60%.

Taxes matter. A lot. First, almost every time an active mutual fund manager makes a trade, our clients pay a tax2. Every time they trim a position, our clients pay a tax. Every time a dividend gets paid, our clients pay a tax. Every time they do seemingly innocent rebalancing, our clients pay a tax. Yet portfolio managers, for over 75 years, have blithely ignored this inconvenient truth. They are not evaluated on after-tax performance. They don’t care because they’re not paid to care. That’s problem one.

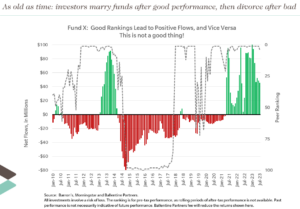

Problem two is human nature – the behavior of investors themselves. When assessing which fund manager to hire, our brains are wired to believe that good past performance must mean good future performance. The problem: decades of research and even SEC-mandated warnings written on every mutual fund prospectus remind investors that it is simply not true. Yet this flawed ipso facto logic is entrenched in the American psyche – a Federal Reserve Bank working paper3 estimated that a fund upgrade to a Morningstar 5-star rating results in a 53% increase in new money inflows.

The opposite behavior also holds: poor performance often leads to investor outflows. For tax-exempt investors, a divorce has no costs. For taxable investors, divorce triggers expensive taxable gains.

As it turns out, a marriage to Fund X would have been a rocky one, with periods of horrific performance.

See the chart below, which shows the rolling 5-year rankings of Fund X, the dotted line. Then we layered net flows into and out of the fund, the green and red bars. The pattern is clear. Money flows in after the fund does well and vice versa. For example, Fund X had fantastic short-term performance in 2011 and 2012, improving to top decile. Money in. Then performance faltered badly starting in 2014, and for half a decade, Fund X hovered in the bottom quartile, at times the worst-performing fund in its class. Tough to stay married. Money out. Chasing performance by flitting from one fund to another is rarely a good idea. But for taxable investors, that bad idea is compounded: a tax to get into Fund X…another to get out.4

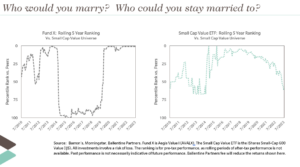

Now let’s look at our second fund, a U.S. small-cap value ETF, a simple, unmanaged, low-cost option that tracks the S&P 600 Value index. SPIVA reports5 have been tracking the performance of index-linked strategies vs. active managers for over 20 years, and their studies show that unmanaged indices show high persistence, that is, they demonstrate good to excellent performance over time, without oscillating too much.

See below. The chart on the left is that same rolling 5-year ranking of Fund X but without fund flows. The chart on the right shows the S&P Small-Cap 600 Value ETF. Remember that this ETF competes in the exact same universe as Fund X. The two funds, over the past decade, had essentially identical after-tax returns. Importantly, both returns ranked in the top decile. But which one was easier to stay married to: Fund X or the ETF?

The table below also shows that the overall experience of owning the ETF would have been much more pleasant. It never once, over the past 10 years, dipped into the bottom quartile, while Fund X spent nearly 40% of its time there.

These two funds delivered essentially the same excellent after-tax returns, but the odds of you actually banking those returns would have increased dramatically with the ETF option if for no other reason than you would never have been tempted to divorce it.

1 The name of the actual fund is not that important to the point of the paper, as the lack of persistency of most funds is well-documented. But it was the Aegis Value I Fund (ticker symbol AFAVX). We did not cherry-pick this fund to do the analysis; quite the opposite, it was Barron’s who cherry-picked it as an excellent fund; we just dug a little bit deeper in our analysis to make a different point.

2 I’m taking a bit of editorial license with this statement, as it’s not technically true. Since markets tend to go up over time, however, it is more often than not the case that active managers are selling appreciated stocks, triggering a capital gains tax.

3 Star Power: The Effect of Morningstar Ratings on Mutual Fund Flows, Diane DelGuercio and Paula A. Tkac, working paper series. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, August 31, 2001.

4 This assumes the investor sold out of one fund to buy Fund X. In both instances, it assumes fund appreciation.

5 SPIVA (S&P Index Versus Active) report, U.S. Persistence Scorecard Year-End 2022, published by S&P Dow Jones Indices.

About Pete Chiappinelli, CFA, CAIA, Chief Investment Officer

Pete is Chief Investment Officer at the firm. He is focused primarily on Asset Allocation in setting strategic direction for client portfolios.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.