I joined the asset management industry straight out of college back in the late 1980s. I worked for a few years, went on to get my MBA, and then I decided to take a small detour from asset management to get a “real job” for a company that actually makes things. Like all newly-minted MBAs, I had grandiose ideas of working for an important global titan — leading a cracker-jack team, making new and cool products, solving gnarly logistical supply-chain issues, and creating hip and memorable advertising and media campaigns. Basically conquering the world.

Reality was a bit different for me. Sometimes the projects are bit more mundane.

I got the “global” part right, at least. I was hired by Unilever, the massive Anglo-Dutch packaged goods and beauty products company that markets its vast array of brands in every corner of the world. I would bet money that if you were to open your refrigerator, kitchen pantry, or bathroom vanity right now there would be some Unilever products sitting there. They are huge.

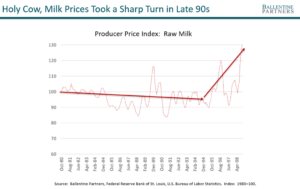

I got to work on one of their largest high-profile brands, Ragu pasta sauce. They called it the Big Ragu and for good reason. Pasta sauce is big business in this country. Ragu commanded over a 42% market share, generating over $500 million in sales, and it had been a steady and growing contributor to Unilever for decades. At the time I joined in the mid- 90s, however, Ragu was under tremendous pressure. For the first time in its history, the Big Ragu was witnessing an actual decline in sales and profitability for two reasons. First, the low-carb diet craze was taking root; the Atkins diet manifesto had landed on the NY Times bestseller list, ominous news for my brand. Pasta was enemy number one, not good news for, you guessed it, pasta sauce! More relevant to my story, however, costs were rising for COGS, or Cost of Goods Sold, painfully similar to today’s inflationary environment. Natural gas prices, which had been relatively steady for some time, were jumping materially. What does natural gas have to do with pasta sauce? Plenty. The costs of fertilizer, derived from natural gas, to grow the tomatoes, garlic, and basil were rising. Crude oil prices had jumped 78% from 1994 to 1997 so the delivery costs to transport those heavy glass jars was rising. Milk —which makes parmesan and romano cheese, key ingredients to Ragu’s recipe — rose dramatically in price after a decade of relative price stability.

There was no way Unilever was going to eat all those costs. They had to find a way to pass them along to the consumer. Raising prices, however, was not an option, as it turns out that consumers are highly sensitive to price increases in a competitive category like pasta sauce. In economist-speak, pasta sauce has “high price elasticity and substitutability”; in plain-speak, it means that Classico, Prego, Barilla, store brands, even kind old Paul Newman are constantly breathing down our necks, ready to grab market share if we dared to raise prices. Not an option. So, Unilever had to find a way to pass along the increased COGS without the customer figuring it out.

The solution was to take some costs out of the jar — not by skimping on the quality of the ingredients but by removing two whole ounces from the 28 oz. jar — while keeping the price per jar unchanged. Welcome to shrinkflation, Italian style!

Thus began a whole cross-functional team project. The glass design team needed to find a way to keep the jar looking like nothing had changed. So, they raised the little glass “bump” at the bottom of the jar a few more centimeters. They altered the contours of the jar’s “shoulders”. They tested different label designs to make the jar still appeared nice and fat when sitting on the shelf. They even changed the wording of the smaller 26 oz measurement to “1 lb 10 oz”. Yes, you are correct: the two weights are identical, but focus groups around the country showed that consumers thought the word “pound” sounded better, like they were getting “a lot of pasta sauce for the money”.

They rolled out the new jar, monitoring for any drop in sales volume. Nothing happened. It had worked. And true to the competitive capitalism idea, every single one of our competitors followed suit within the next four to five months. And that is how inflation happens.

Why are we telling this story? Well, obviously, after the past decade of relatively tame inflation we as a nation are experiencing some sizable price shocks. While it feels foreign to you, this is nothing new in corporate America. Company after company, over the decades has dealt with these kinds of issues before, and frankly, they are quite adept at managing through it. In fact, in any competitive industry, senior management is always thinking about how to keep margins constant or growing by passing along costs to consumers. But that can take many forms, as it did with Ragu: reduced use of coupons, or a lower coupon discount strategy, reduced frequency of promotions or “end -aisle” deals, or as my story shows, shrinkflation. The arsenal of tactics and tools companies like Unilever have is profound, but in all cases, inflation is “passed along” to the consumer. For companies who operate in emerging markets, where inflation levels have been consistently higher for decades, management teams there are especially well-versed at wringing out COGS or managing cost-price relationships. Why? In order to survive, that’s why.

Inflation expectations are the highest they’ve been in over 20 years. See the chart above, which tracks the implied inflation expectation embedded in the pricing of bonds. There has and will continue to be lots of chatter in the financial press about how best to prepare an investment portfolio for some unanticipated inflation — talk of timber, resources, oil ETFs, TIPs, etc, etc.. But just remember that good old equities have for years been a very effective “real asset.” In the short term, yes, equities tend to react poorly to unanticipated inflation, but in the intermediate to long term, the companies, products and cash flows represented by those equities are actually the very mechanism through which inflation gets passed through to households. Unilever’s profits don’t get smaller, just their jars of pasta sauce.

About Pete Chiappinelli, CFA, CAIA, Deputy Chief Investment Officer

Pete is Deputy Chief Investment Officer at the firm. He is focused primarily on Asset Allocation in setting strategic direction for client portfolios.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.