Executive Summary

The S&P 500 stock index is now officially in a bear market, having fallen more than 20% since the peak on January 3, 2022. The issues facing investors in coming quarters are daunting, yet these too shall pass. While not minimizing the risks ahead, we note a number of positive factors that lead us to believe that if a recession is forthcoming, it is likely to be short and shallow. We outline several adjustments we’ve made to client portfolios to reflect the new economic reality, and we resist the temptation to make wholesale changes based upon short-term thinking.

What Just Happened?

After posting three straight years of exceptional performance that saw the S&P 500 double since the COVID outbreak in March 2020, stocks have experienced a painful decline in 2022. And on June 13, the U.S. stock market officially entered into bear market territory, defined as a 20% drop from peak to trough. Unfortunately, the weakness in the stock market was due in no small part to a meaningful jump in interest rates, which has weighed on bond prices as well. Usually a reliable hedge when stocks are falling, fixed income has so far not provided the normal counterweight this time around.

We noted several risks to equity markets as we entered 2022: high valuations, excessive optimism, and the onset of tighter monetary policy intended to tame rising levels of inflation. Nonetheless, we were comforted by strong consumer and corporate balance sheets, a diminishing impact from COVID on supply chain bottlenecks, still-solid growth in forecasted earnings and real GDP, and the positive track record of equities as a reliable long-term inflation hedge.

Unfortunately, several things happened in the first few months of the year which added to the risk side of the ledger. First, China reinstituted a total economic lockdown in Shanghai to curb a nascent outbreak of COVID, which derailed immediate hopes for a resumption of normal global trade activity. Second, after months of saber rattling, and to the surprise of many experts, Russia invaded Ukraine. Economic sanctions in Russia and physical destruction in Ukraine caused severe disruptions in exports from both of these countries, including among others: oil, natural gas, wheat, and sunflower oil that are critical to the delivery of a panoply of finished goods. This further added to economic uncertainty and most surely added to inflation woes. And then, in the last few days, as hopes and market expectations that inflation had “turned the corner”, a surprising CPI inflation report came out, higher than expected. This unnerved investors and ratcheted up expectations for even stronger monetary medicine from the Fed. The fear is that, in their attempts to return inflation to more comfortable levels, the Fed might tighten too aggressively, triggering a recession. Investors responded by pushing stock prices through the psychological bear market barrier of a 20% loss.

Expectations for the near future

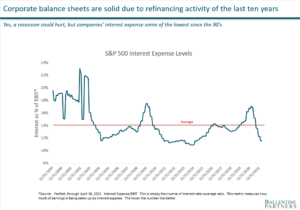

Our base case is for the U.S. economy to narrowly miss a recession in the next year, and if a recession does occur, it should be shallow and short. Both corporate balance sheets and US consumers enter this period in strong condition, which should presage a generally good economy over the next few years. Corporate balance sheets — after years of refinancing at some of the lowest interest rates in U.S. history — are in solid shape. Today is most definitely NOT a parallel to the 2007-2008 era where corporate debt had gotten out of control.

The U.S. consumer, which drives two-thirds of our economy, is also in some of the best shape in decades. Rising wages, low unemployment, a pent-up desire to consume after years of “lockdown”, and again, a rock-solid balance sheet, also give us some comfort that consumers can tolerate higher interest rates without a severe pullback in spending. The US consumer has done a stand-up job of getting her financial house in order, as evidenced by manageable debt servicing levels as indicated in the chart below. The Federal Reserve tracks whether U.S. households are vulnerable, related to their ability to pay their debt. In 2008 consumers had borrowed so much that the recession’s pain was magnified. This time around, it is quite the opposite: while rising costs for food and energy are certainly problematic for many, the US actually began 2022 with some of the healthiest balance sheets in over 40 years.

Economic forecasting is difficult in any environment, so our forecasts, and everybody else’s must be taken with a grain of salt. We acknowledge the Fed has a difficult balancing act: tighten too much and a recession ensues; too little and inflation becomes permanently entrenched in people’s expectations. We also acknowledge the potential for many other risks getting worse: continued supply chain issues, a worsening of the Ukrainian situation, extended China lockdowns, etc. Chief among our concerns is the risk that inflation will remain more persistent.

The financial press, as you are likely aware, is generally not a great source of comfort or nuanced information. Headlines like, “worst week since 2020” are intended primarily to get eyeballs rather than to inform. For example, some of these headlines have highlighted the ominous “inverted yield curve” — when the yield on the 2-year is higher than the 10-year Treasury — as a sign of a looming recession. Rarely do these same articles include that this indicator has a pretty poor predictive track record, so much so that our Fed does not even use it in its leading economic indicators. In fact, the main metric they do use, the spread between the 3-month T-bill and the 10-year Treasury yield is giving no such warning signs.

While headlines about inflation draw attention, inflation metrics are exceedingly complicated and contain numerous variables, making it easy to cherry pick sensationalized tidbits. Indeed, the recent headline CPI print moved higher, and that spooked the markets. But keep in mind that “core” CPI, which strips out the very volatile food and energy prices was actually down modestly in the month of May. True, it was not down as much as many had hoped, but it was down, nonetheless. It is entirely possible that we are indeed about to turn the corner on inflation, albeit with some fits and starts along the way. That would be normal in a complex and adaptive system like the U.S. economy. It’s never a straight line.

We’ve written extensively about the folly of trying to forecast short-term movements by anticipating the market’s direction and making major changes in advance of those moves. In addition to getting both calls right (when to get out and when to get back in), taxable investors must also factor in the tax liability associated with selling securities at a gain. Most often, it ends badly for those who attempt it. In an inflationary environment however, this strategy is even less effective. An investor sitting on cash because they fear higher inflation will lock in a loss of real purchasing power if they are right and will miss strong market returns if they are wrong.

This does not suggest that anyone should sit by idly in 2022. We’ve made a number of modest and prudent shifts within our portfolios this year. We reduced our U.S. equity exposure back in February, shifting a bit towards Europe, which was trading at some of the most attractive levels we’ve seen in over 30 years. Further, where appropriate, we’ve taken advantage of the market weakness in both stocks and bonds to realize losses in order to reduce future tax liabilities. We’ve also begun shifting some of the fixed income allocation we’ve held in a very short-term tax-exempt fund to longer-dated, high yielding municipal bonds, which are now generating income of more than 8% on a taxable-equivalent basis.

The bottom line is that there are things to be doing and things not to be doing. Chief among the things to do is to remain focused on the long-term, and to stick by your investment strategy. Sell-offs like these are not only normal, they are indeed part of the bargain we make when we invest in equities. Even though the 10-year period ending 2021 was one of the best decades we have experienced in the U.S., in 7 of those 10 calendar years, there were double-digit intra-year drawdowns. We continue to look for ways to either reduce poorly compensated risks, look for oversold markets, and use tax loss harvesting to mitigate tax drag.

About Bruce D. Simon, CFA, CPWA®

Bruce is a Partner and the Director of Research at the firm. In addition to working directly with a number of family clients, Bruce serves on Ballentine’s Investment Management Committee, which is responsible for the oversight of all of the investment activities for the firm.

About Pete Chiappinelli, CFA, CAIA, Deputy Chief Investment Officer

Pete is Deputy Chief Investment Officer at the firm. He is focused primarily on Asset Allocation in setting strategic direction for client portfolios.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.