Ominous headlines from the financial press imply a “bad start” of the year bodes poorly for 2022 and beyond. But is there more to the story?

This week, there was a bit of sound and fury in the financial press, with April’s challenging performance. It was, no doubt, a painful month, with the S&P 500 down -8.8%, MSCI EAFE down -6.5%, and MSCI Emerging Markets down -5.6%. More importantly, April’s declining markets added to losses already suffered in the first quarter, so the first four months of 2022 have not been pleasant for anybody. We have clearly entered a period of increased volatility.

But there was a particularly cynical edge to some of the headlines and commentary. An extra dose of misery and foreboding, if you will. Market observers were using all sorts of ominous historical references, implying something quite sinister was afoot. Let’s take a quick look at some of the headlines from the popular financial media:

CNBC: Stocks off to worst start since 1942

MarketWatch: A rough 4 months for stocks: S&P 500 books the worst start to a year since 1939

CNN Business: The S&P is having its worst start to a year since 1939

Barron’s: Stocks: Worst Start to the Year in Decades

And not to be outdone:

Bloomberg: S&P (SPX) Having Worst Start to Year Ever

While these market historians could not agree on whether this was the worst start since 1942 or 1939 or in all of human history, the message was clear: things are bad and likely to worsen. The implication was that the first four months of the year are somehow predictive or correlated to what’s around the corner. This got me thinking. What have the first four months told us historically? Is there any actual information in the cruel month of April, after all?

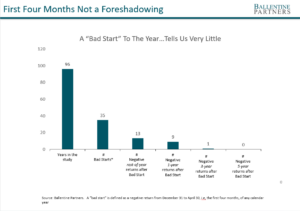

The chart below uses data on the U.S. stock market returns going back to 1926. There are 96 calendar years to study. Thirty-five of them suffered a “bad start,” which is defined as delivering negative returns for the first four months, from December 31 to April 30. As you can see, bad starts are by no means uncommon, as they have occurred 36% of the time in the past near-century.

But do they tell us anything about the returns we should expect going forward? Are they actually bad omens, as the dire headlines imply?

Not necessarily, as only 13 of the bad starts had negative returns in the “rest-of-year,” that is, the remaining eight months from April 30 to December 31. Do they signal bad returns for the next 12 months? Evidently not, as only 9 of those 35 bad starts had negative returns one year hence. Do bad starts foreshadow further losses three years or even five years down the road? It does not appear so. There was only one incident of a negative 3-year return after an initial bad start; further, there were no historical examples of a negative 5-year return after a bad start.

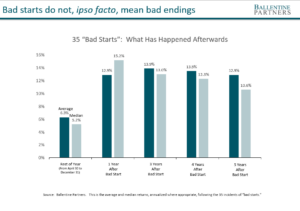

In fact, if history repeats or even closely rhymes, a bad start to any calendar year has actually been a good omen, the exact opposite of what the financial press would have you believe. When we look at what kind of returns investors received after bad starts, the picture is encouraging, not foreboding. See the chart below, which looks at the average and the median for rest-of-year, 1-year, 3, 4, and 5-year returns, after getting off to a bad start.

I want to be clear. There are lots of things to worry about today. Any of you, or we here at Ballentine, could easily rattle off a laundry list of legitimate concerns about the state of the world and risks to the capital markets: the war in the Ukraine and risk of escalation, rising interest rates, rising inflation, potentially shrinking profit margins, continuing supply-chain snafus, China lockdowns and economic slowdown, high valuations, etc. The list is daunting. If markets do indeed do poorly for the rest of the year, or over the next year, any one or any combination of those factors will likely be the culprit. But in the fog of admittedly disarming market declines, let’s not panic: if history is any guide, the bad start to 2022 does not ipso facto mean we are in for more trouble.

About Pete Chiappinelli, CFA, CAIA, Deputy Chief Investment Officer

Pete is Deputy Chief Investment Officer at the firm. He is focused primarily on Asset Allocation in setting strategic direction for client portfolios.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.