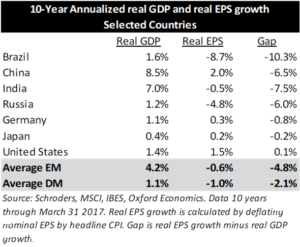

During the nine years ending in 2018, real GDP among emerging developing countries expanded at a 7.0% annual rate, more than three times the growth rate of the United States.1 In China, the largest country in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, real GDP grew at an astonishing 8.5% annual rate, and India grew by 7.0%.2 The strong growth in these emerging market countries has lifted millions of consumers out of poverty and into the ranks of a modest middle-class lifestyle. And this trend is likely to continue: McKinsey estimates that China’s “upper middle class” will grow from 36 million households in 2012 to 193 million by 2022, and private consumption of this group will increase by more than 22 percent annually over this period.3

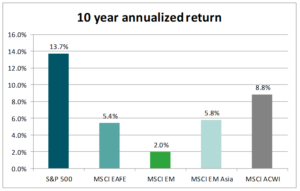

Many professional investors correctly forecasted the spectacular growth of emerging market economies and the growing appetite for consumer products as affluence increased. Yet for all this economic progress, emerging market equities have failed to deliver the kind of performance that would be expected to accompany strong economic growth. According to Pimco, the S&P 500 generated a total annualized return of 12.2% from March 2009 to August 2019, while the MSCI Emerging Market Index gained only 0.4%.

Source: Morningstar Direct. Returns are trailing 10 year annualized, through October 31, 2019.

What accounts for this apparent anomaly? And, for investors, are there reasons to stick with this theme despite the disappointing performance of the last decade?

Why emerging market stocks have underperformed

Economic theory teaches us that a company’s stock price is largely determined by its expected earnings growth in the future, discounted by an appropriate interest rate that accounts for the unpredictability of those future earnings. In allocating to emerging market stocks, investors assumed that high GDP growth rates and growing middle class affluence would generate a surge in profits that would drive emerging market equities to above-average gains.

Over the last decade, that assumption has proven to be false. Earnings growth among major emerging market countries have lagged far behind real GDP growth. In contrast, earnings growth in the United States has generally kept pace with the slower growth in real GDP, supporting the substantial outperformance of US equities over this period.

So what accounts for the yawning gap between real GDP growth and real earnings growth among large emerging market economies? There are several possible explanations for this result, including:

- Measurement issues: Economists have long been skeptical of government-published GDP growth rates in emerging market countries, especially China;

- Reliance on exports: Generally speaking, EM countries are more heavily reliant on exports for GDP growth. So corporate profits may be driven more by global rather than domestic demand, softening the link between GDP and earnings;

- Structural differences between the economy and the public stock market: In emerging market countries, the number and composition of privately-held companies may be materially different than those represented in public market indices. For example, if consumer-oriented companies are under-represented in public markets, stock markets would fail to capture much of the explosive growth in consumer demand.

- Share dilution: On average, share dilution among emerging market companies has been much higher than that of developed market companies. When firms issue more shares, they dilute the per-share earnings power of the company by spreading the earnings over a larger share base. So even though aggregate profits may be keeping pace with GDP, per-share earnings may lag.

Beyond the GDP/EPS gap, there is one other factor that has dampened the returns of emerging market stocks for US investors over the last decade: the US dollar. Over the past 10 years, the US Dollar Index (DXY) has appreciated approximately 26% against a trade-weighted basket of other currencies. A strong dollar reduces the return on foreign investments when local currency is converted back into dollars.

Will faster growth translate to better results in the future?

After 10 years of disappointing returns, investors are rightly skeptical of the ability for emerging market stocks to outperform the United States over the next decade. Fundamentally, emerging market economic growth is noticeably slowing, and the threat of a protracted trade war with the United States continues to dampen sentiment for EM equities in the short run.

Longer term, the fundamentals remain quite solid. According to JP Morgan, almost 1.5 billion people are expected to enter the middle class in EM Asia between 2020 and 2030, almost 90 percent of the global growth in this segment. Spending among the middle class is expected to grow even faster than the population. JP Morgan estimates that EM economic growth should exceed developed market growth by approximately 2.5 percentage points per year over the next 10 to 15 years.4

So will the growth of the middle-class Asian consumer finally translate into better performance for skeptical investors?

We think so, and here’s why:

- Changing composition of the market: In the past, the largest sectors of emerging market economies were related to commodities, a highly volatile sector. In the past 10 years, commodity-oriented firms have shrunk from 30 percent of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index to 15 percent, which the consumer segment has grown from 11 percent to 30 percent4. A larger weight in consumer companies is likely to increase the earnings growth rate of the MSCI EM Index, and reduce the gap between reported GDP and earnings growth.

- Increased transparency and improved regulatory framework – One potential benefit of the ongoing trade dispute with China may be a more level playing for companies doing business there. A reduction in regulatory obstacles and improved governance as China moves toward developed market status could improve the business climate and allow companies to drop more of their revenues to the bottom line.

- Reorientation toward domestic demand – As the size of the domestic consumer population swells and demand surges, Asian economies will see domestic consumption become an increasingly important component of real GDP, tightening the linkage between GDP and earnings growth.

- Lower returns for US stocks – With US stocks trading near all-time highs, the relative valuations between US and emerging market equities look especially appealing right now for EM. If returns for the US stock market fail to maintain the exceptional pace of the last decade, EM equities are likely to attract more capital from investors looking for higher returns.

- Weaker US dollar – The dollar has experienced a strong run over the last decade as the US economy recovered from the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-’09. Dollar strength tends to move in long cycles. With the federal deficit approaching $1 trillion, we anticipate a gradual decline in the value of the dollar, improving the returns on foreign holdings for US investors.

With global growth expected to be scarce in coming years, we believe investors will increasingly focus their attention on where growth can be had at reasonable prices. The explosion of the middle class Asian consumer is expected to continue apace for the next decade. This time, we believe investors will be rewarded for their patience.

1 Source: Factset.

2 Source: “GDP and earnings growth in emerging markets: A loose connection”, Schroders, September 2017.

3 “Mapping China’s Middle Class”, McKinsey Quarterly, June 2013. Upper middle class is defined as annual income of $16,000 to $34,000 in 2010 US dollars.

4 “Reemergence of EM equities: The dawn of the EM consumer”, JP Morgan Asset Management, November 2019.

Learn more about Bruce Simon, our Director of Research.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable but has not been independently verified. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.