Written by Ben Daly, CFA, CAIA, CFP®, Senior Investment Advisor and Ryan Bachur, CFA, Senior Portfolio Manager

For over three generations of professional investment management, rules, guidelines, and heuristics were developed for endowments, foundations, pensions, and other tax-exempt institutions. They became the “law of the land,” ensconced in the investment and finance curricula taught around the world. Tragically, however, the entire investment management industry and academia completely ignored the plight of taxable investors, who need to think differently than their tax-exempt colleagues. Countless examples exist. This paper focuses on an important topic that has beguiled taxable investors for decades, the funding of private investments. Taxable investors seeking to harness the attractive returns available in private markets must recognize that most of these vehicles are funded over time as capital is called to fund underlying investments. The source of funding future capital calls – and potential capital gains taxation – is a critical input in evaluating the value added by these private investments and is often overlooked by investors. Set cash aside for expected capital calls? For how long? Use a public proxy that approximates the return of the private vehicle? Or use some other approach? The purpose of this paper is to explore alternative methods for funding capital calls and to provide a framework for making these decisions. Crucially, though, it was developed exclusively for taxable investors.

Executive Summary

Building a successful private investment program requires a very active level of portfolio management, especially in the early years as net asset value (NAV) is built up toward its target level. This paper is focused on the ramp-up period of private investment programs (where the current net asset value (NAV) is below the target NAV and assumes the portfolio is cash flow neutral). Both when and where in the portfolio funds are sourced for capital calls can have a meaningful impact and is often overlooked. What makes Ballentine’s framework unique is our focus on after-tax portfolio-level returns over the long term. Every client portfolio and situation is unique, but we carefully consider several different factors each time capital is needed to fund the private investment portfolio. This requires a holistic approach to portfolio management not only across asset classes, sectors, and geographies but also between the public and private allocations in the portfolio.

Four-Part Framework Overview

- Understand the tax implications of sourcing capital across all holdings in the portfolio.

- Generally, fund capital calls as they are received, as opposed to in advance.

- Under normal market conditions, fund private commitments from their counterpart in the public portfolio. Furthermore, look to avoid selling relatively cheaper segments within broader asset classes.

- Under extreme market conditions, consider funding commitments from a different asset class altogether.

1. Background: Understanding the tax implications of sourcing capital across the portfolio and putting the framework to use

A thoughtfully constructed private investment program can add value to client portfolios that can tolerate the illiquidity associated with long-duration private investments. Significant time is spent deciding upon an appropriate target allocation to private investments, modeling out cash flows, conducting manager due diligence, and reporting performance. However, the process by which capital commitments are sourced from other parts of the portfolio is often overlooked. When working with taxable investors, it is important to agree upon this framework for how capital will be sourced prior to any capital being invested.

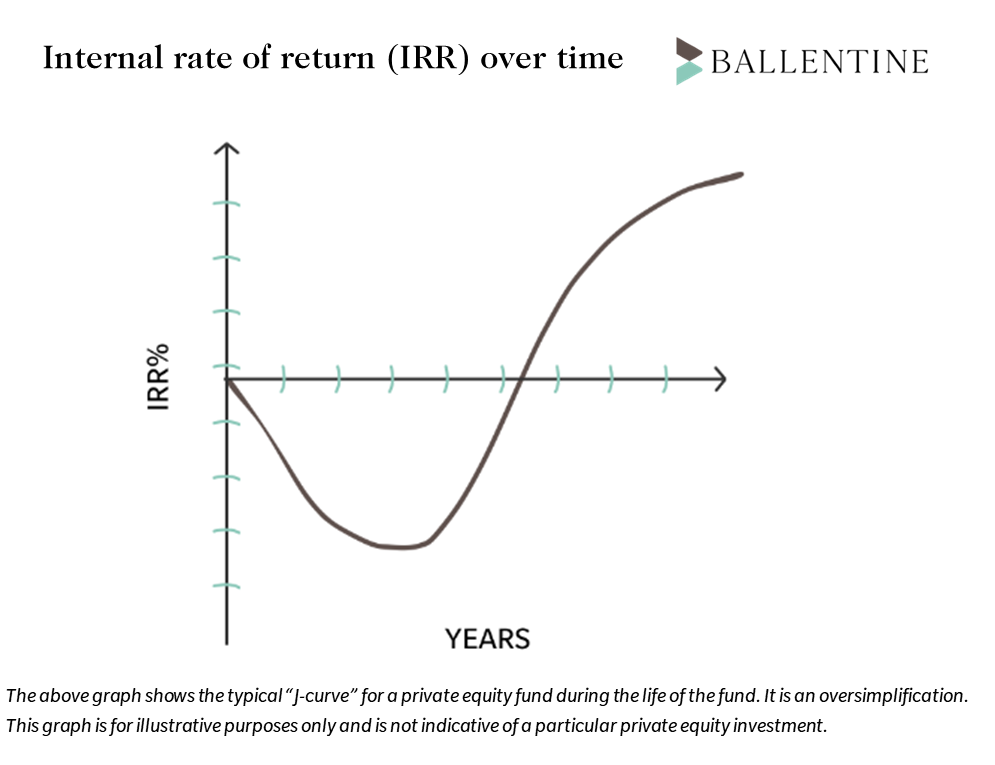

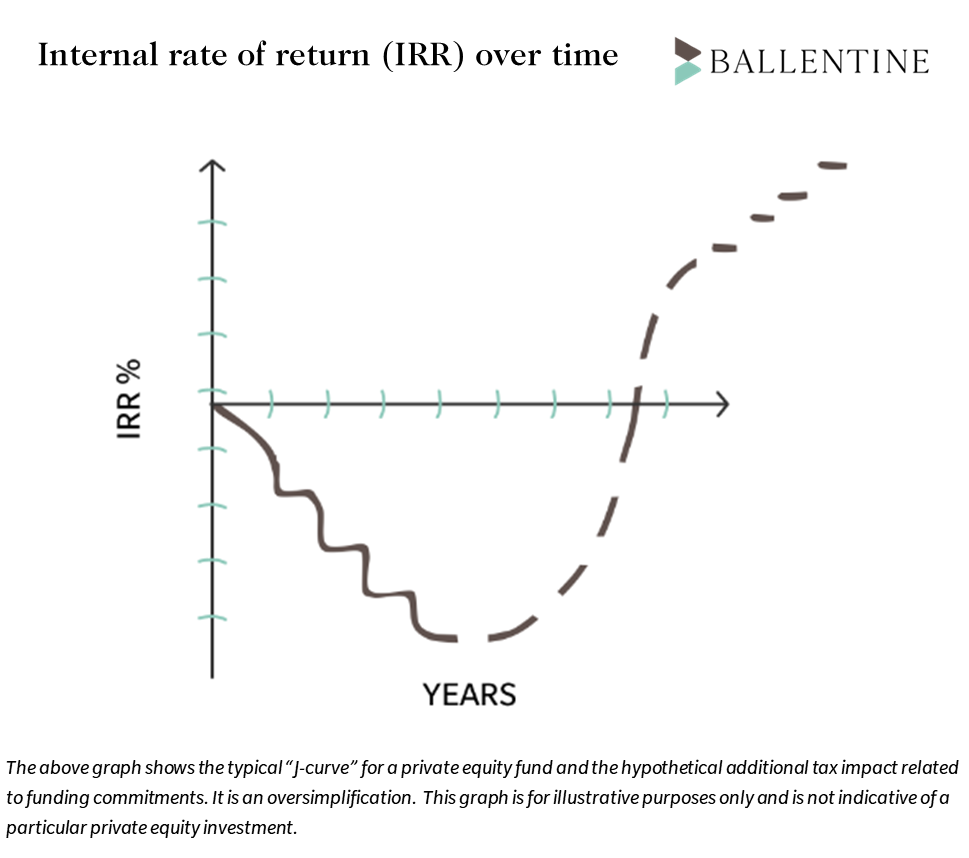

In private markets, the “J-curve” is the term commonly used to describe the tendency of private equity funds to produce negative returns in the early years and then generate increasing returns in later years as the underlying investments mature. The negative returns in the early years typically result from investment costs and management fees and could be affected by early-year write-downs on underperforming investments. For taxable investors, there can also be an additional incremental drop in return that is attributable to private investments in their early years. As investments outside of the private portfolio need to be sold to generate cash to fund capital commitments, taxable capital gains may be triggered, and an associated liability is generated which must be paid the following year. This results in a J-curve that resembles more of a saw blade.

The “illiquidity premium” is the incremental return that compensates investors for owning private assets in exchange for foregoing the liquidity available in the public markets. Allocators and portfolio managers often report on private investment fund performance by comparing the returns to public market equity indices on a pre-tax basis and often highlight the added value they have generated by capturing this illiquidity premium without considering taxes paid at both the onset and exit. Putting aside taxes paid at the onset for a moment (which will vary for each investor) as well as taxes paid upon realization, investors typically require private investments to generate annual returns between 300-500 basis points above a public market equivalent in order to justify the illiquidity. Taking this a step further, there should be an additional premium required above the standard illiquidity premium to compensate investors for the tax liability generated from both funding private investment commitments as well as the gains incurred from exiting investments, in order to justify their inclusion in the portfolio. This additional return should be equal to the tax liabilities generated from the investment during its holding period.

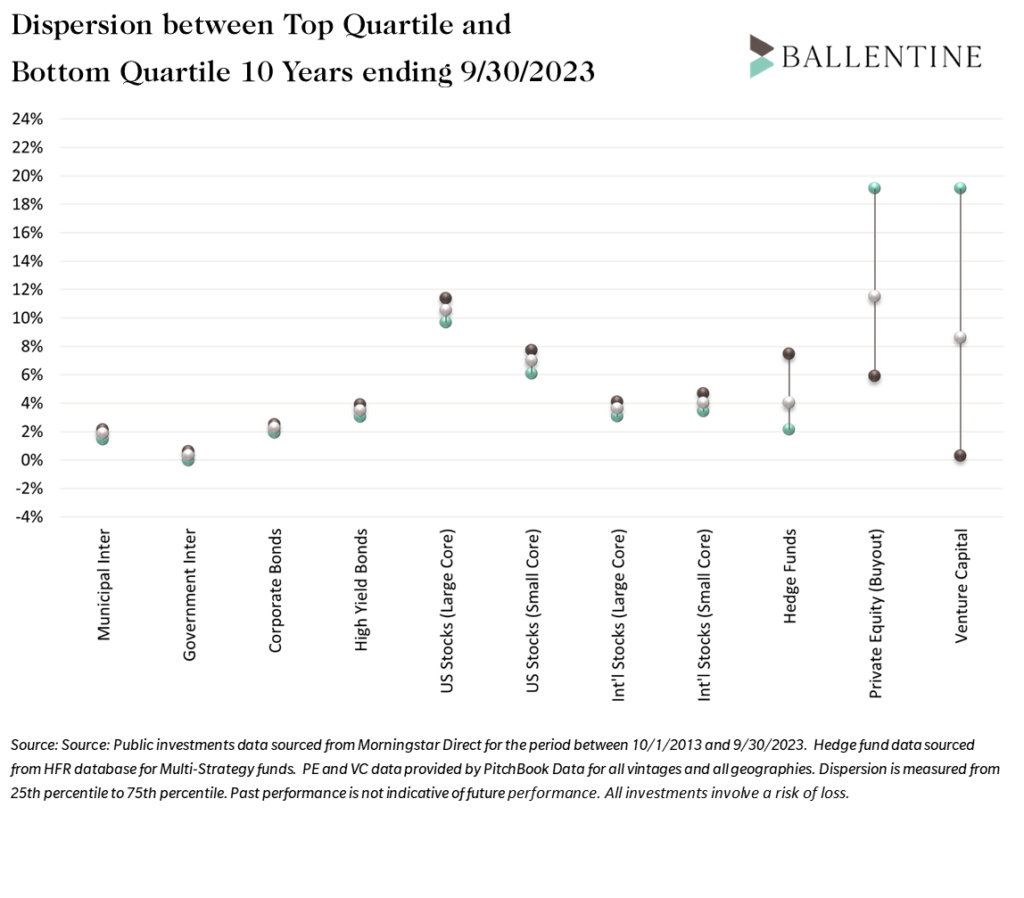

The after-tax hurdle is, and should be, very high for allocating capital to an illiquid investment. Since the dispersion of returns between top and bottom-performing managers within private investment asset classes is very wide, manager selection is incredibly important. Ballentine’s research team goes through a rigorous and extensive due diligence process focused on identifying and partnering with general partners who we believe can generate returns above this after-tax hurdle. As seen in the graph below, this return is typically only achieved by top-performing funds in any given vintage year.

Unlike public securities which can in theory be held indefinitely, private funds have a finite life. While we can’t control the realization of taxes generated by private fund managers, we do have control over when and where capital is sourced from the portfolio to fund these investments. Ballentine utilizes a framework to guide client portfolio managers in the decision-making process for when and where to source capital. Many factors that should be carefully considered in this process including the cost basis of current investments, rebalancing & risk exposure, relative valuations, risk tolerance, and liquidity needs.

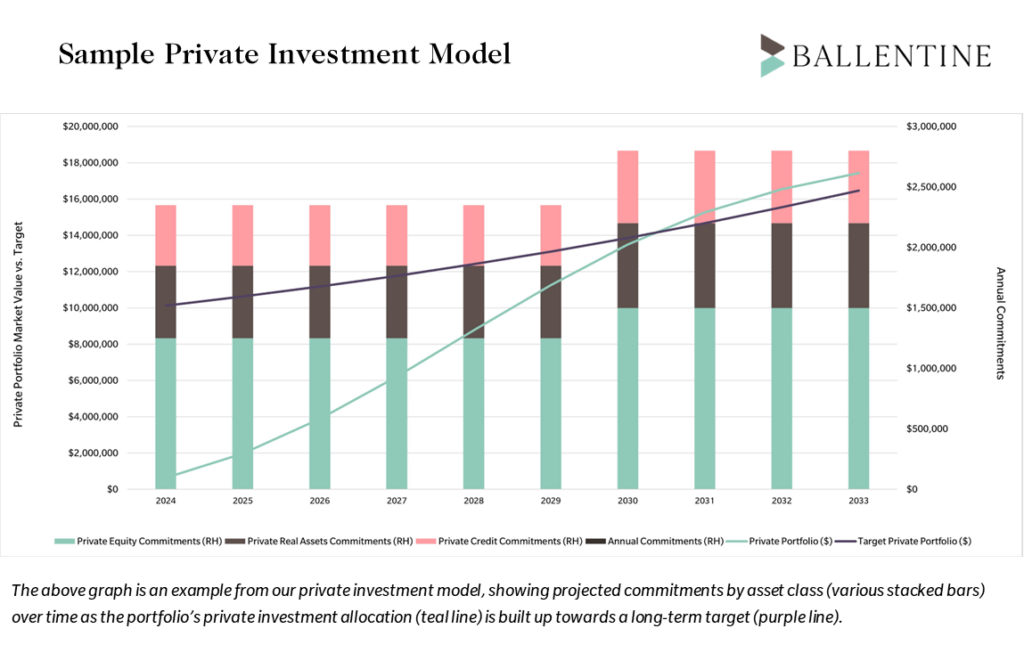

Cash flow planning and management is an essential part of any successful private investment program. Ballentine uses a proprietary model to help estimate cash flows from private investment programs. Using historical data from funds across our database, the model takes into account how quickly capital is typically called (and distributed) across the various types of private strategies in order to generate forecasts of future cash flows. Of course, we have no way of precisely knowing when capital will actually be called or distributed, so it is important to remember that models are just a tool that help to provide a good starting point in the decision-making process. The model is used to generate recommended annual commitment amounts that will allow the private investment NAV to build up toward its target in a reasonable amount of time, after which this part of the portfolio becomes self-funding. That is, distributions from current investments can be used to fully fund ongoing capital commitments to new investments.

2. When to fund? Generally, fund capital calls as they are received, as opposed to in advance.

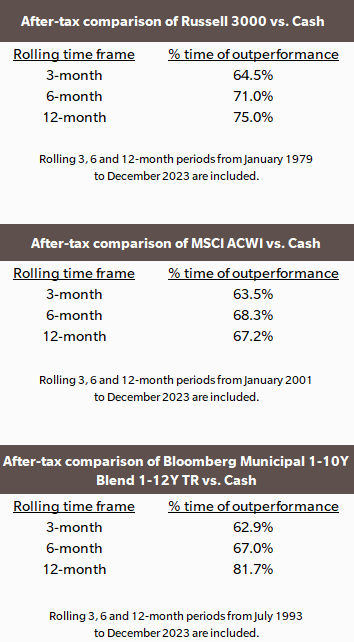

Allocators and client portfolio managers have different strategies for planning to fund these liabilities, from both a timing and portfolio location perspective. With regards to timing, one common approach used by allocators is to set aside in cash a reasonable estimate for the next three, six, or twelve months of capital calls. Reasons include the desire to know cash will be there when needed (sleep well at night), as well as operational (less frequent transactions). However, we believe this approach is not optimal, as US equities have outperformed cash on an after-tax, rolling 3-month basis about two-thirds of the time since 1979.1 On an after-tax, rolling 6-month and 12-month basis, US equities have outperformed cash by 71% and 75% respectively. The equity risk premium demands a higher rate of return to compensate an investor for the higher volatility. Bonds have also outperformed cash, albeit to a lesser degree, over the same time frames (see tables below). We believe it is important to educate the investor on the impact of cash drag and to weigh that against their risk tolerance and comfort level with generating cash as needed, instead of in advance, to satisfy capital calls. Of course, there may be times when it could be advantageous from a tax perspective, such as near the end of the year, to raise cash ahead of time. An example would be taking gains in a year where the clients’ effective tax rate will be lower than the following year. Ballentine works closely with clients’ CPAs in order to understand when that may be prudent.

3. Where to source funds?: In normal market conditions, fund private commitments from their counterpart in the public portfolio.

With regards to the location in the portfolio of the funding source, again allocators and investors have different methods. A few common approaches include funding private equity commitments pro-rata from across the public equity portfolio or holding unfunded commitments for private equity in a small-cap equity index like the Russell 2000. Generally, most portfolio managers will fund private investment capital calls for various types of strategies from the public risk-equivalent part of the portfolio (i.e. use public equity to fund private equity, public real assets to fund private real assets, public fixed income for private credit, etc.). From a risk perspective, such a method makes intuitive sense in that the transactions keep the relative asset allocation and risk profile generally the same. This method is our preferred starting point, and we generally look to fund pro rata from across an asset class when valuations are within reasonable ranges from their historical averages (within ~1.5 Standard Deviations). Of course, embedded capital gains will have a large impact on the ultimate decision and are a major component of our overall process and framework.

Next, we drill down further to understand relative valuations between segments within broader asset classes. Ballentine’s asset allocation team utilizes a dashboard with two components, valuation and momentum, to quantify the attractiveness of the various segments relative to each other. For example, within global equities, are US equities cheap or expensive relative to non-US equities? Are large caps cheap or expensive relative to small caps? We always seek to act from a position of strength in managing the portfolio and will look to avoid selling cheaper assets whenever possible. If emerging markets equities are historically cheap relative to US equities, but non-US developed equities are within a normal range in terms of valuation, instead of selling pro-rata across the public equity portfolio to fund a private equity commitment, we would look to sell more US equity and less EM equity, of course after taking into consideration the level of appreciation of the underlying positions.

4. Sourcing funds in extreme market conditions? Consider funding commitments from different asset classes.

When market conditions are at or near extreme levels, Ballentine’s framework includes taking this a step further by considering funding from a different asset class altogether. For example, if public equity markets have sold off by 25%, one should consider whether funding a capital call from fixed income is warranted. This allows us again to act from a position of relative strength in the portfolio and not have to sell into weakness on assets that have significantly declined in value over the short term. One can draw parallels with this approach to rebalancing a more traditional portfolio by selling fixed income and buying equities after a significant drawdown in public equity markets. Sometimes portfolio cash flows can cause the asset allocation to deviate from its long-term targets. Such times can also provide an opportunity to source capital calls from other asset classes in order to help rebalance back to targets.

Properly managing private investment programs for taxable investors requires comprehensive portfolio management work. Without a disciplined framework for sourcing funds and managing cash flows, results from private investment programs can be significantly reduced due to tax consequences. Since every client situation is different, it’s critically important to have a thorough understanding of their entire financial picture and take a holistic view that factors in taxes into every decision. We believe Ballentine’s four-part framework is a key component to achieving successful client outcomes for those investing in private markets.

1 US equities performance measured by the Russell 3000 Total Return Index. Global equities performance measured by the MSCI ACWI Total Return Index. Cash performance measured by the ICE BofA US 3M Trsy Bill Total Return Index. After-tax returns for US equities were estimated by applying a long-term tax cost ratio (trailing 15-year) on the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund ETF (VTI) as a proxy for the Russell 3000. After-tax returns for global equities were estimated by applying a long-term tax cost ratio (trailing 15-year) on the iShares MSCI ACWI ETF as a proxy for MSCI ACWI. After-tax returns for cash were estimated by applying the maximum federal income tax rate of 40.8% on the ICE BofA US 3M Trsy Bill Total Return Index.

*IRR (Internal Rate of Return)– the discount rate where the sum of discounted cash flows and the discounted valuation is equal to zero. This is a return metric commonly used to measure performance in private equity type investments where capital is called and distributed over time.

About Ben Daly MBA, CFA, CAIA, CFP®, Senior Investment Advisor

Ben is a Senior Investment Advisor at the firm. He provides clients with customized investment advice tailored to achieve their goals and objectives. In his role, Ben works closely with clients to develop and execute a comprehensive investment strategy and assists with all aspects of clients’ investments.

About Ryan Bachur, CFA, Senior Portfolio Manager

Ryan is a Senior Portfolio Manager at the firm. In his role, Ryan works with the senior investment team in all aspects of the portfolio management and investment process. This includes the development of client investment plans, trading and investment implementation and meeting with clients to review their portfolios.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.

Please advise us if you have not been receiving account statements (at least quarterly) from the account custodian.