Authored by Pete Chiappinelli, CFA, CAIA, Partner & Chief Investment Officer and Christopher C. Chandler, CFA, CAIA, Partner & Chief Investment Officer

Summary Bullets:

- Market volatility is more likely driven by uncertainty in policies (which are hard to plan for) rather than actual economic damage.

- Scary headlines help sell advertising, but they may not be reliable sources of investment advice. Our view is that the impacts of tariffs and DOGE will be directionally negative in the short term, but not to the degree that the financial press would have you believe.

- There are mitigating factors to the headwinds of tariffs and DOGE. Tariffs are on goods, not services (and our GDP is primarily driven by services). Tariffs are likely to be limited in scope: by products, by countries, by duration, etc.

- DOGE’s impact will likely be diluted by legal challenges, political realities, and the eventual absorption of laid-off employees by the private sector, state and local governments, and other federal agencies.

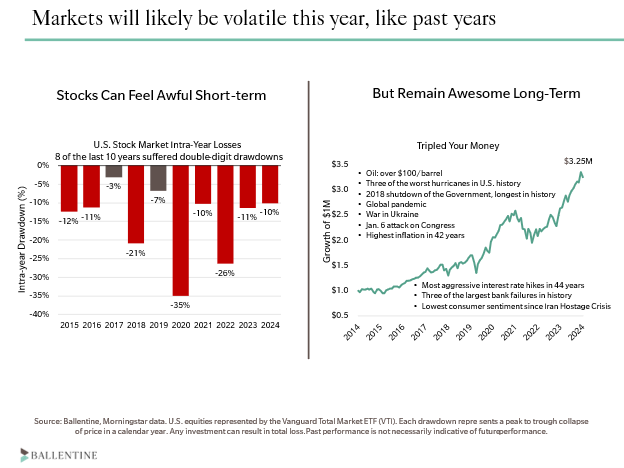

- As we stated in our January letter, it was highly likely that the market would, at some point, suffer a double-digit drawdown, if for no other reason than they are normal and occur with regularity.

- There will eventually be clarity. When that happens, markets, businesses, and consumers will adjust to the new reality and carry on, because that’s what they’ve always done.

There are lots of scary headlines regarding tariffs and DOGE. We encourage you to stay calm and carry on.

Part I: Tariffs

Let’s tackle tariffs first. What are tariffs and why do countries use them? Tariffs are taxes, officially called import duties. They have been used by countries throughout history for what economists call “the three R’s”: revenue, restrictions (to protect domestic industries from competition), and reciprocity (as a bargaining chip). Tariffs were a major source of tax revenue for the first third of our nation’s history. Economic policies changed notably after the Great Depression, resulting in the passage of The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1948, which helped usher in an era of low tariffs. Global trade accelerated as further treaties and agreements moved toward an era of free or freer trade. The average duty on goods subject to a U.S. tariff was less than 4% for the past quarter-century.

And then everything changed.

The new administration is now proposing large tariffs, dusting off the “three R’s” playbook to raise government revenue, encourage re-shoring of manufacturing, and as bargaining chips for other desired economic and social goals (immigration restriction and fentanyl crackdowns, specifically).

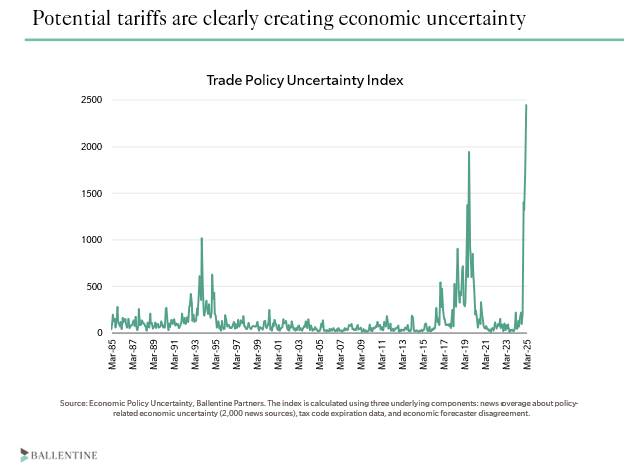

The stock market reaction and the financial press headlines, however, have focused on the potential negative outcomes. Why? First, the magnitude of the tariffs proposed by the current administration represents a significant break in U.S. policy. Second, there is strong fear that tariffs could usher in a period of stagflation – higher prices plus slower growth, neither of which is desired. Finally, and related, the capital markets have been unnerved by tariffs, as they can dent profits, cause consumers to slow down purchases, and cause companies to slow down investment, creating a self-perpetuating cycle. The optimism of CEOs of both large and small companies – buoyed originally by the promise and prospect of business-friendly policies such as reduced regulations and lower taxes – has turned decidedly pessimistic. Tariffs, originally thought of more benignly as potential negotiating tactics, are now viewed as major frictional costs and disruptions to supply chains and operations, generally. Finally, the rapid changes in strategy – sometimes reversing within hours – have become distractions from other more desirable goals. In a word, tariffs have created massive uncertainty. See the chart below. And the markets do not like it. The S&P 500 has lost, as of this writing, close to 10% from its February 19 high, further fueling the scary headlines.

So, let’s discuss Ballentine’s views on tariffs at a high level.

Are tariffs inflationary, or will they slow down the economy? Yes.

There are two mechanisms of inflation. The first: U.S. importers, facing the additional tax, will pass some or all of the tariff burden onto consumers through higher prices. The other mechanism is that domestic producers, seeing higher prices on imported competitive products, may opportunistically follow suit.

But tariffs can also have a simultaneous anti-growth, or deflationary effect, as higher prices typically lead to reduced demand. When consumer goods become more expensive, households may cut back on spending, leading to an overall economic slowdown. This negatively impacts hiring, wages, investment in new capacity, etc. In this way, tariffs act as a brake on economic momentum. More alarming, there is fear (and evidence) that retaliation against the U.S. will spiral into a global trade war, slowing global growth.

Mitigating factors:

Despite the financial media’s scary headlines, we believe the impact of tariffs may be more muted. First, tariffs apply only to goods, not services. Given that services make up roughly 70% of U.S. consumer spending, the majority of economic activity remains untouched.

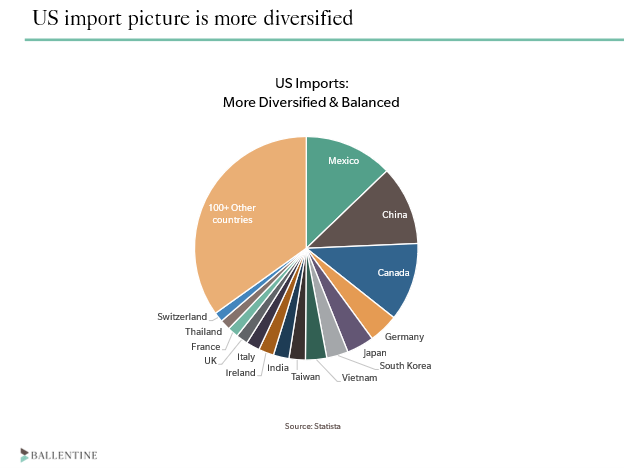

Second, the current set of proposed tariffs is relatively narrow in scope. The media focuses on trade disputes with China, Mexico, and Canada, but these three countries account for only approximately one-third of total U.S. imports. The remaining two-thirds come from a diverse spectrum of countries. Now, the situation remains fluid, and we concede that the administration has talked about raising tariffs on other countries, but the focus has been on these three countries so far. Also, many of the proposed tariffs have exemptions, diluting their impact.

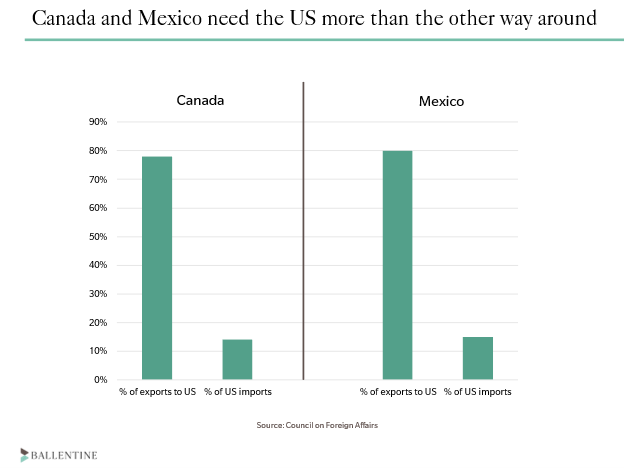

Third, it’s plausible that the current administration still views them primarily as a shorter-term negotiating tool rather than a permanent policy shift. The on-again, off-again horse-trading nature of what is playing out certainly lends credence to this idea. If tariffs are being used to pressure trade partners into concessions on other issues—such as immigration enforcement, a crackdown on fentanyl distribution, or reshoring of some manufacturing—then their long-term impact on the economy could be less severe than feared. Canada and Mexico, in particular, are highly dependent on U.S. trade, with 90% of their exports going to the U.S. So if tariffs are indeed a negotiation tool, this puts the U.S. in an extremely strong negotiating position. And the administration is simply playing its strong hand.

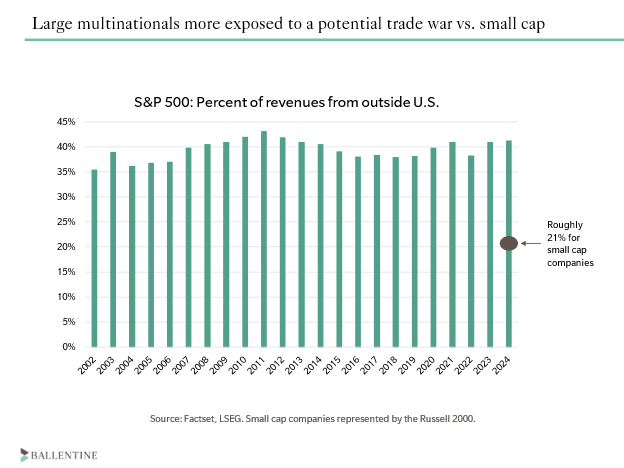

Finally, small companies are the backbone of the U.S. economy. Roughly half of all Americans work for companies with fewer than 100 employees, and 99.9% of U.S. businesses are small. Most small businesses do not have complex global supply chains, and most of them generate the vast majority of their revenue from domestic clients. The Russell 2000, a proxy for publicly traded small-cap companies (not small in the traditional sense, but small by public company standards), derives only 21% of its revenue from outside the U.S. The point is that most companies are shielded from a global trade war, should one ensue. Mega-cap multinational tech companies, on the other hand, are much more exposed, and their stock prices have taken a disproportionate hit. That’s why we are thankful that in client portfolios, we’ve been tilting away from these large-cap companies since last summer.

Part II: DOGE

The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) was established with a mission to streamline federal bureaucracy, significantly reduce government spending, and address the deficit. Its primary rationale was appealing: shrinking the expansive footprint of government. However, this initiative has stirred controversy, particularly surrounding fears that substantial federal layoffs could drastically elevate unemployment rates, amongst other worries beyond the scope of our commentary.

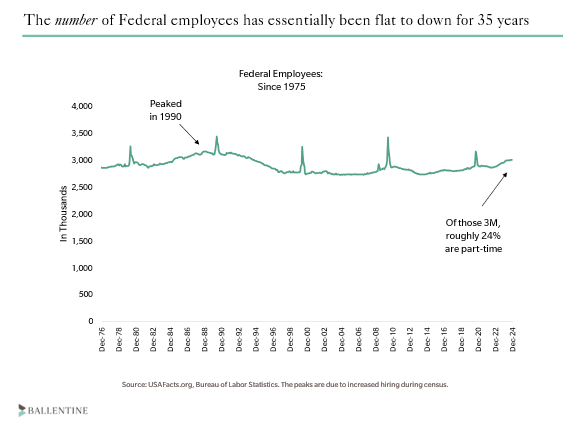

Despite widespread anxiety, data suggests that DOGE’s impact on employment may be less severe than anticipated. The federal civilian workforce numbers under three million employees, a figure that appears substantial at first glance. Yet, several mitigating factors indicate that the effect on unemployment would be manageable.

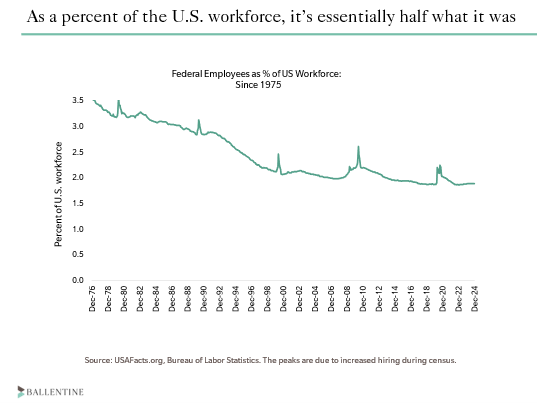

First, the number of federal employees has essentially remained flat for 35 years, peaking back in 1990. Since then, despite population and economic growth, the total workforce has been declining, not growing. More importantly, when examined as a percentage of the broader U.S. workforce—which exceeds 160 million—the federal employment rate has decreased by essentially half. See charts below.

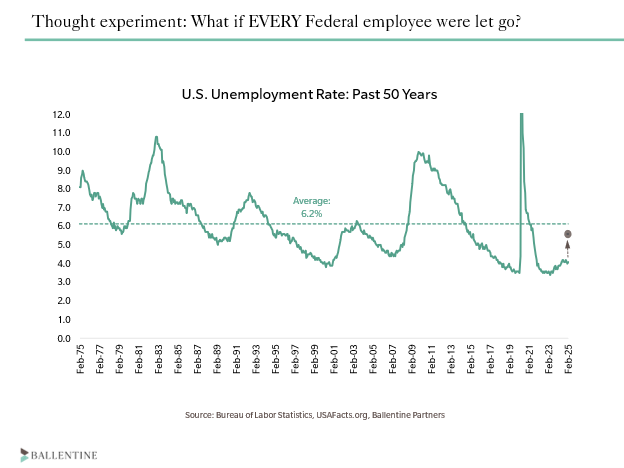

A thought experiment underscores this point: imagine if DOGE terminated every federal employee, an absurd scenario. The unemployment rate would only rise to approximately 5.8%, still below the 50-year average of 6.2%. The U.S. economy grew and prospered for many decades with much higher levels of unemployment.

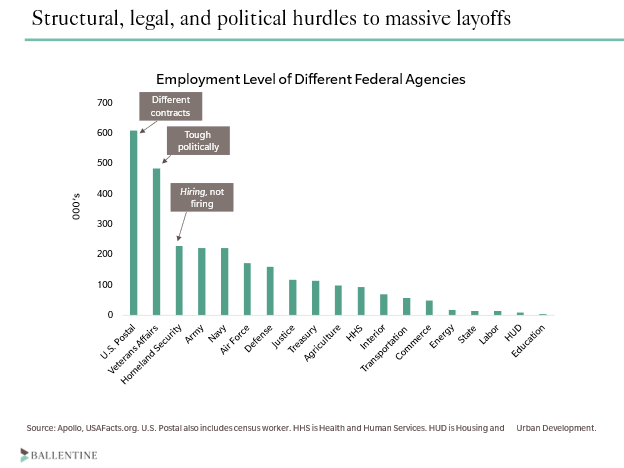

To state the obvious, DOGE layoffs will not be that drastic. Various analysts estimate the number to be around 300,000, or closer to 10%. But even that may be aggressive given structural, political, and legal realities, especially when we look at the employment picture in the chart below. The largest federal employer, the U.S. Postal Service, operates under a unique, self-funded arrangement with separate labor contracts, rendering large unilateral reductions improbable. Reducing doctors, nurses, and hospital staff for veterans’ care is problematic for obvious political reasons. The third-largest agency, Homeland Security – the agency responsible for enforcing immigration restrictions – is hiring people, not firing them. And the next three – the Army, Navy, and Air Force – have historically enjoyed strong political support from the conservative wing, so large-scale reductions there are challenging politically. All the headlines these days seem to be on efforts to eliminate the Education Department entirely, but as you see in the chart, you could eliminate twenty Education Departments, and it would still be a rounding error in terms of making a dent in the total picture. Finally, there will be and have been challenges and judge rulings that DOGE does not even have the authority to enact these reductions-in-force.

Additionally, natural attrition and retirements—which occur regularly—and absorption into other federal or state agencies and the private sector will soften DOGE’s employment impacts. The private sector alone has recently demonstrated robust job creation, generating approximately 150,000 new positions in the past month.

In summary, although DOGE initially sparked fears of significant economic disruption, our take is that the impact will be more tempered.

Concluding Thoughts

The situation is literally changing day by day, if not hour by hour. This back-and-forth has not inspired confidence, as evidenced by market gyrations. The risks of creating a bout of inflation or a bout of economic slowdown (or both) are very real. And we all need to get mentally prepared for increased market volatility over the next few months. In our January letter, we indicated that a double-digit market correction at some point during 2025 would be likely. It would be completely consistent with the past: double-digit corrections occurred in 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2018, and 2016…you get the point. These market drawdowns create tremendous angst. And we understand the temptation to try to dodge them. Our advice is to stay the course. Why? Eight of the past ten years suffered double-digit mid-year drawdowns. Yet in that ten-year period, equity markets still tripled your money.

Our base case started the year with a view that economic growth would be “solid” for reasons that bear repeating: a strong consumer, 60-year lows in unemployment, downward-trending inflation, rising real wages, booming AI demand and its required energy and infrastructure investments, AI efficiency gains, cheap valuations in certain pockets of the market, the prospect of lower regulation and lower taxes, the highest profit margins on record, and double-digit earnings growth. This partial list presented a very solid tailwind. But we also acknowledged the very real risks to this base case, tariffs and high valuations among them. It’s entirely possible that our “solid” base case may still prevail, but the shorter-term road ahead has demonstrably gotten rockier in the past three weeks. We don’t want to sound Pollyannaish.

Scary headlines in the financial media help sell advertising, but they may not be good sources of investment advice. Our view is that the impacts of tariffs and DOGE will be directionally negative in the short term, but not nearly to the degree that the financial press would have you believe. There are mitigating factors. And there will eventually be clarity. When that happens, markets, businesses, and consumers will adjust to the new reality and carry on, because that’s what they’ve always done.

About Pete Chiappinelli, CFA, CAIA, Chief Investment Officer

About Christopher C. Chandler, CFA, CAIA, Chief Investment Officer

Important Disclosure

All commentary contained within is the opinion of Ballentine Partners, LLC. and is intended for informational purposes only. The content is current as of the date indicated and is subject to change without notice. Select statements that are not historical facts may be forward-looking statements based on our current expectations of future events. Information obtained from third-party sources is believed to be reliable; however, the accuracy of the data is not guaranteed and may not have been independently verified.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.