Over the years, we have noticed a distinct pattern to the mistakes private investors make. In this article, we describe some of the most common mistakes and also provide guidance about how to avoid making them.

By “private investors” or “individual investors” we mean investors who must pay income taxes each year on their investment income. We include trusts in the definition of private investors because most trusts must pay tax on investment income each year.

1. Failure to focus on net after-tax returns.

Your net return is your gross return minus fees, trading costs and other expenses you incur to manage your investments, minus taxes you pay on your investment income. Your net return is the only return that matters.

2. Misunderstanding the concept of risk.

Individual investors tend to equate “risk” with loss of capital. For many years, investment professionals have taught private investors that portfolio “risk” can be measured by the annual standard deviation of returns. Both of those definitions are likely to lead a private investor astray and may prevent the investor from reaching his or her goals.

For individual investors, the most useful definition of “risk” is the possibility that you will fail to meet one or more of your investment objectives. Prudent selection of risk exposures and management of those risks is essential for meeting an investor’s goals. Investors cannot avoid risk. Although investment theory postulates a “risk-free” investment, in the real world there is no such thing.

3. Failure to establish a strategic asset allocation and stick with it.

As advisors, one of the biggest challenges we face is convincing clients to stick with their strategic asset allocations during a major market correction. Most of us hate to see the value of our investments decline. Investors react to market downturns by shifting assets out of equities and into bonds or cash.

In his famous book, Winning The Losers’ Game, Charles Ellis eloquently described the problem:

“Holding onto a sound policy through thick and thin is both extraordinarily difficult and extraordinarily important work. This is why investors can benefit from developing and sticking with sound investment policies and practices. The cost of infidelity to your own commitments can be very high.”1

4. Chasing investment returns.

Many studies of investor behavior have shown that the average mutual fund investor earns considerably less than the funds in which they are invested. Most of the difference in performance is accounted for by investor behavior. Investors tend to purchase investments that have recently performed well and sell investments that have recently performed poorly. That is, investors tend to “buy high” and “sell low” – the opposite of what they should be doing. The average investor retains an equity mutual fund for only about 5 months. So much for long-term investing!

5. Misunderstanding the illiquidity premium.

The term ‘illiquidity premium” refers to the incremental return that is theoretically available to investors who can tolerate the risks associated with buying and holding investments that cannot be easily traded.

The misunderstanding lies in the relationship between risk and return. We frequently hear investors say, “If you want a higher return, you have to take more risk.” The logical structure of this statement is: more risk produces higher return. That is not sound logic.

It would be more accurate to say:

“If you are thinking about taking more risk – such as illiquidity risk – then you should do so only if you believe the investment will produce sufficient incremental return over a liquid alternative investment to justify the additional risk.” The logical structure of that statement is: more risk requires the expectation of a higher return, which is quite different from prior statement.

6. Lack of awareness of psychological biases influencing investment decisions.

A new field of economics called “behavioral finance” was invented in 1955. Classical economic theory was based on the “rational man” hypothesis. The problem is that “rational man” exists only in the economists’ imaginations. Real people behave quite irrationally, especially when money is involved. All of us, including investment professionals, are prone to errors in judgment if we fall prey to our irrational tendencies.

You should seek to gain some familiarity with the cognitive biases that are most important for investment decision-making. Those biases include:

- Recency bias

- Availability bias

- Anchoring

- Confirmation bias

- Loss aversion / endowment effect

- Hindsight bias

7. Misunderstanding your rate of consumption.

We find most of our clients don’t have accurate data about their spending, and when asked to estimate it, they substantially underestimate their spending. Obtaining an accurate estimate of your future cash requirements is essential to long-term income planning, particularly if one is planning to make large lifetime gifts to family and charity.

8. Misunderstanding the impact of cash flows on portfolio management.

Your net additions or withdrawals are a key factor in determining how easy or difficult it is to manage your investment portfolio. A portfolio with frequent cash in-flows is far easier to manage than a portfolio with frequent cash withdrawals. The management problem becomes acute when the cash withdrawals are so large the portfolio value shrinks and its ability to fund future cash withdrawals is in doubt.

9. Failure to understand the impact of inflation on investment returns.

Inflation is like a hidden tax. It silently erodes the purchasing power of money. If inflation is low, over short periods of time its impact is likely to escape notice. However, over a decade or longer periods, investors who ignore the impact of inflation do so at peril to their wealth.

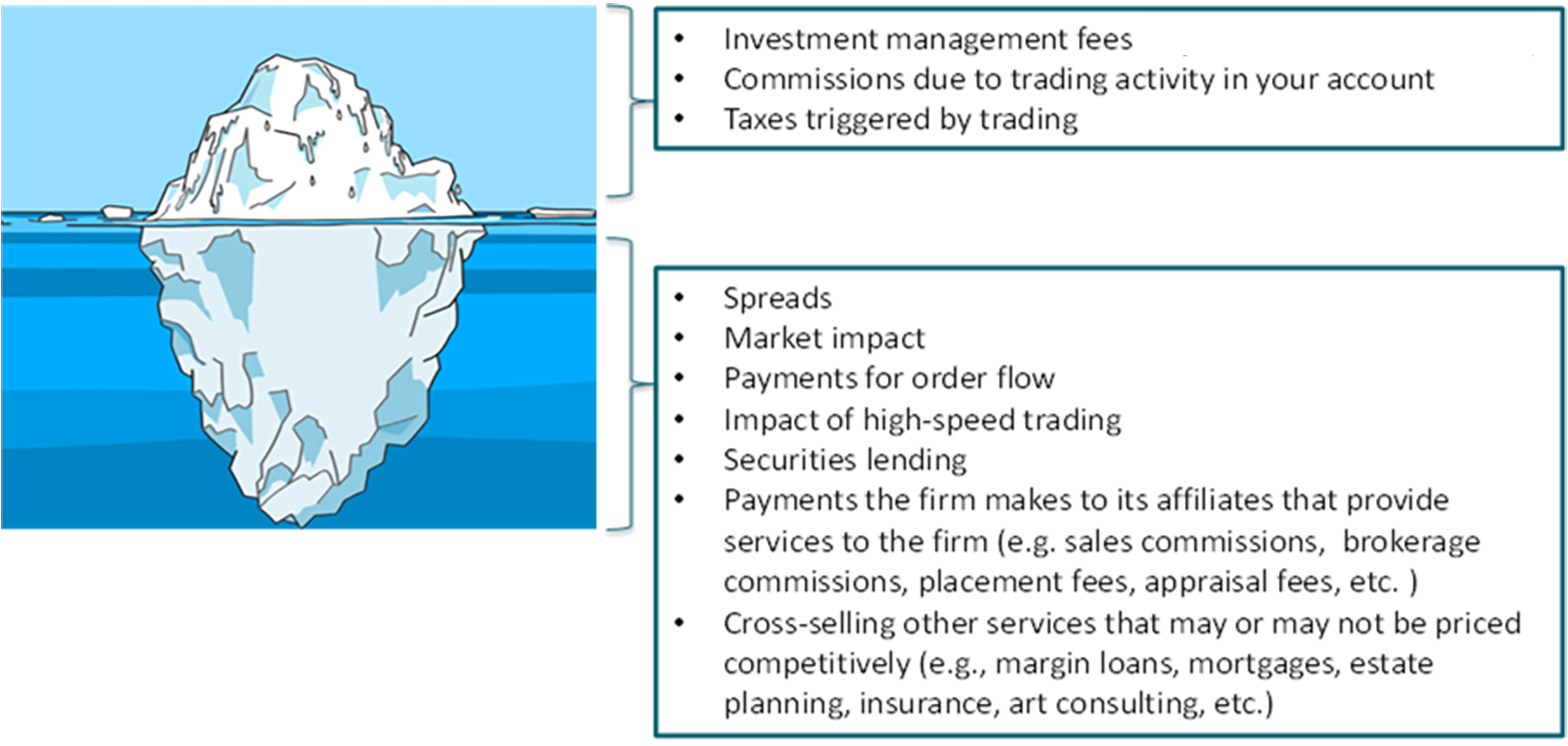

10. Underestimating the costs of conflicts of interest.

Conflicts of interest cost investors, particularly private investors, far more than most investors realize. The following graphic illustrates that the costs that are most visible to you may be just the tip of an iceberg. Your total investment costs include the portion of the iceberg you cannot see. Unfortunately, broker-dealers are not required to provide full disclosure. In many cases, investors simply have no means to determine the total costs they are incurring.

1 Ellis, Charles, Winning the Loser’s Game, McGraw-Hill, 2017.

About Roy C. Ballentine, ChFC, CFP®

Roy is the Executive Chairman and Founder of the firm. Roy dedicates his time to thought leadership, strategic oversight of client engagements, and coaching and training our team members.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.