If you are feeling a bit nervous these days, know that you have a lot of company. The world is serving up no shortage of things to worry about. 40-year highs in inflation. Fears that the Fed will overshoot its money tightening policies and plunge the U.S. economy into recession. Russia’s merciless attacks on Ukrainian cities that seem to draw NATO closer and closer to actual conflict. Continued supply chain issues. China’s rolling lockdown of cities and slowing economic growth. New strains of COVID. Should I stop now? Because I could go on. Quite easily, actually.

For the capital markets, however, it’s never been an issue of whether there is risk. There is always risk of loss. Thus it ever has been. Thus it ever shall be. So investors should not be asking, “Is this asset risky?” Or, “Is the market risky?” That’s the wrong question. Instead, we should be asking, “How is the market pricing this risk?” I don’t pretend that that is an easy question to answer, either, but it is the more correct framing of the investment puzzle. We do, however, know that the market has done a serious re-pricing of risk in the first six months of 2022. We all experienced a rapid and painful correction, one for the history books, evidently, if you pay attention to the financial headlines. NASDAQ and U.S. small cap growth stocks both lost nearly 30% of their value, a punishing response to the worries around the world. Trillions of dollars of market value have evaporated. Sadly, bonds, which had been a stalwart counterweight to equity risk for much of the last four decades, failed as well. Just when we needed the anti-correlation qualities of high-quality bonds the most, they, too, lost value, with the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond index down over 10% at the same time.

But if the capital markets have taught us anything over the last 40 years, it is that when ever-present worry reaches extreme levels, we can actually worry a little bit less. And that’s where we find ourselves today. The mood of the nation, on so many dimensions that we have lost count, is extremely dour. Survey after survey tells us what we have sort of suspected for some time: there is a dark foreboding in the air, a feeling that something bad is right around the corner. Strangely — although not really, as there is a non-intuitive logic to it — these extreme pessimistic moments have historically been turning points for the capital markets. And make no mistake, we are at or near some extremes.

See the chart below. The Conference Board has been doing consumer research for nearly 40 years. They ask a litany of questions to get at the mood of the country on a continuous and systematic basis. One of the questions they have been consistently asking over this time frame has to do with the stock market, specifically whether someone thinks markets will decline over the coming year. As you can see, there is a ton of noise to this metric, so it must be taken with all the usual grains of salt. There really is not much predictive power in the year-by-year reading. At the extremes, however, it appears we need to take notice, but as a contrarian indicator. The worry measure went to extreme levels in 1991, yet if you had bought U.S. stocks when your neighbors were the most worried, you would have compounded your wealth at over 19% per year over the ensuing three years. It happened again in 2003 when U.S. consumers suffered a “peak worry” moment. Yet 2003 marked the end of the Tech Bubble correction and the beginning of a half-decade powerful rally in stocks. The exact same thing happened again in March of 2009, which was another extreme reading. Yet March of 2009 was the exact bottom of the market, and from that high-water worry mark came a three-year rally of 23% annually and one of the best decades in U.S. stock market history.

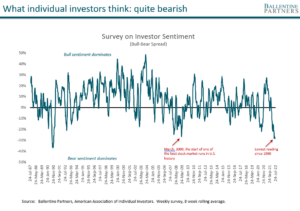

So that’s the story with people on the street, your average citizen. The same holds true, however, for those people who pay more attention to the markets than the average citizen — not professionals, per se, but self-identified private investors who observe and participate in the stock market on a regular basis. Below is a chart from the American Association of Individual Investors, which has been polling their members for almost 40 years on their bullish or bearish leanings. The Bullish-Bearish spread (that is, what percent are bullish minus what percent are bearish – a low reading means the bears outnumber the bulls) is one such quantitative metric they’ve been tracking in their survey. As above, there is a ton of statistical “noise” to this data set. But it apparently has shown to be telling at the extremes. The same as before, the bears outnumbered the bulls profoundly in March of 2009, the exact wrong time to bearish. And today, that bearish sentiment has exceeded that extreme reading — this reading is the most bearish since 1990, over 30 years ago.

Finally, there is the professional investor class, the ones who work in the capital markets every day and have devoted their careers to it. Yet here, too, a study from Bank of America showed that even professional investors tend to get extremely bearish and allergic to risk at precisely the wrong time. In other words, professional investors back in the late 2008/early 2009 period were taking the least amount of risk at the very moment that markets were bottoming, selling at the lows, so to speak. Today, their bearish sentiment is at a new extreme.

Are current extreme worries the “turning point” for markets? We have no idea. Are average citizens right to be concerned about many of the macro risks? Absolutely. Is there risk in the markets today? Wrong question! There’s always risk, but is the market pricing it in? We are certainly not out of the woods with the current retreat of P/E multiples, as they are still high by many historical standards; there may certainly be some additional re-pricing of risk in the coming months or years, even. No single metric, or any collection of metrics, has proven to be effective for predicting the short-term direction of markets. Which is exactly why we avoid playing that game. [For taxable investors, in particular, the frictional tax costs of trying to time short-term movements in the market is a recipe for disaster]. But in a world full of extreme or near-extreme worry — from average citizens to the professional investing class — we can worry a bit less these days. “Risk means more things can happen than will happen” is a famous quote from legendary investor Howard Marks, and it is poignantly reminiscent of Churchill’s timeless story about worry and life, itself.

About Pete Chiappinelli, CFA, CAIA, Deputy Chief Investment Officer

Pete is Deputy Chief Investment Officer at the firm. He is focused primarily on Asset Allocation in setting strategic direction for client portfolios.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.