Introduction

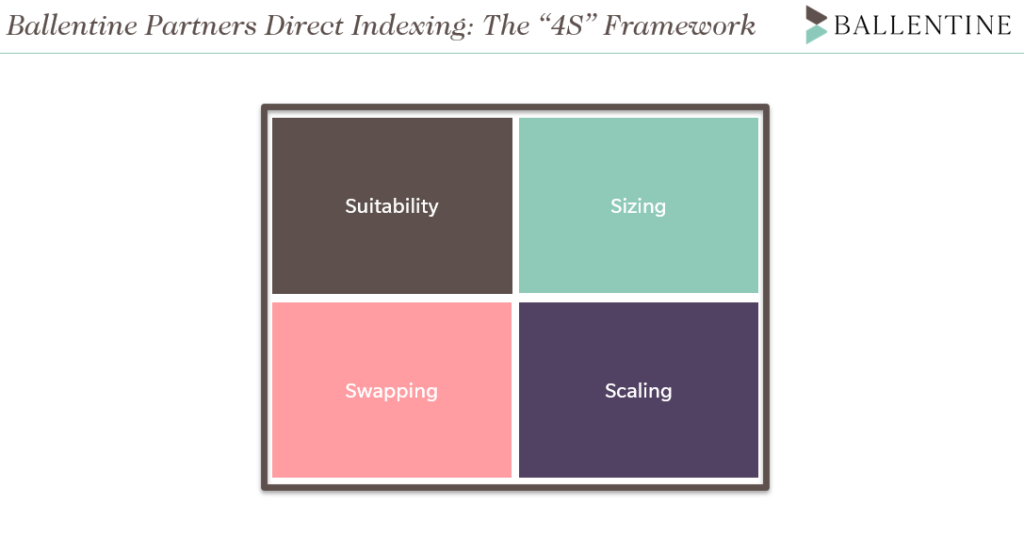

We are big fans of ETFs. But our research shows that investors may see even better after-tax outcomes through direct indexing separately managed accounts (SMAs). The financial industry has also recognized this potential, and the marketing hype has reached a fever pitch. So we yet again must take a skeptical approach as we do with every investment strategy – especially those most heavily marketed by Wall Street. We recognize and are optimistic about the benefits when applied in the right situations, but direct indexing is not a good solution for everybody! We have spent the past year developing a framework to better apply this strategy for the benefit of our clients. We call it the “4S” framework: Suitability, Sizing, Swapping & Scaling.

Suitability

ETFs are the closest thing to a “one size fits all” solution in today’s investing world. They are cheap, efficient, and widely available. And their performance against active peers has been top quartile to top decile over long periods of time.[1] ETFs are simply great vehicles. As a result, we must be confident in the incremental benefits offered by direct indexing. Here is where suitability is extremely important – those benefits are not equally valuable for all investors.

The first “S” in our framework, suitability, addresses the important question: who should use direct indexing? We have summarized what we consider the three most important suitability criteria in the flow chart below: future capital gain expectations, tax rate, and estate plan.

These criteria are key in determining the value of tax loss harvesting – the main value proposition of direct indexing. Tax losses are most valuable when: 1) they can be used to offset future gains, 2) those gains will be taxed at high rates, and 3) tax deferrals are codified into tax savings by the eventual passing of assets to estate or charity.

First, an investor needs capital gains! Offsetting capital gains with tax losses is core to these strategies. One must expect capital gains in the future in order to have something to offset – more on this later.

Second, the rate at which those gains are taxed determines the value of the offset. For example, a top-tax bracket investor in California pays a 37.1% combined marginal tax rate on long-term capital gains. A Florida resident pays 23.8%. Now imagine each has $1 million of capital gains this year, and a direct indexing program offsets those gains. The California investor saved $371,000 in taxes. The Florida resident $238,00. Same gain, but direct indexing had more value to the California taxpayer.

The third suitability criteria is focused on estate planning. Tax loss harvesting, by definition, achieves realized (“harvested”) losses today in exchange for greater unrealized gains within the portfolio. An example: an asset purchased for $100 declines to $80 and is “harvested” to capture a $20 tax loss. The original cost basis of $100 is now lowered to $80. If the position returns to its original $100 value, the owner has a $20 unrealized gain despite “breaking even” on their original investment. What the investor plans to do with their direct indexing assets over their lifetime impacts the balance of this tradeoff. If assets are sold in the future, realizing their gains, then some of the tax benefits of direct indexing are given up via that future tax bill. Taxes are deferred into the future, rather than saved. However, many wealthy investors either hold investments through the end of their lives (passing them into their taxable estate which receives a step-up in cost basis to the current price) or make substantial donations to charity (where unrealized gains are not taxed). Direct indexing can be suitable for investors of either camp but is more valuable for those who do not expect to sell their assets.

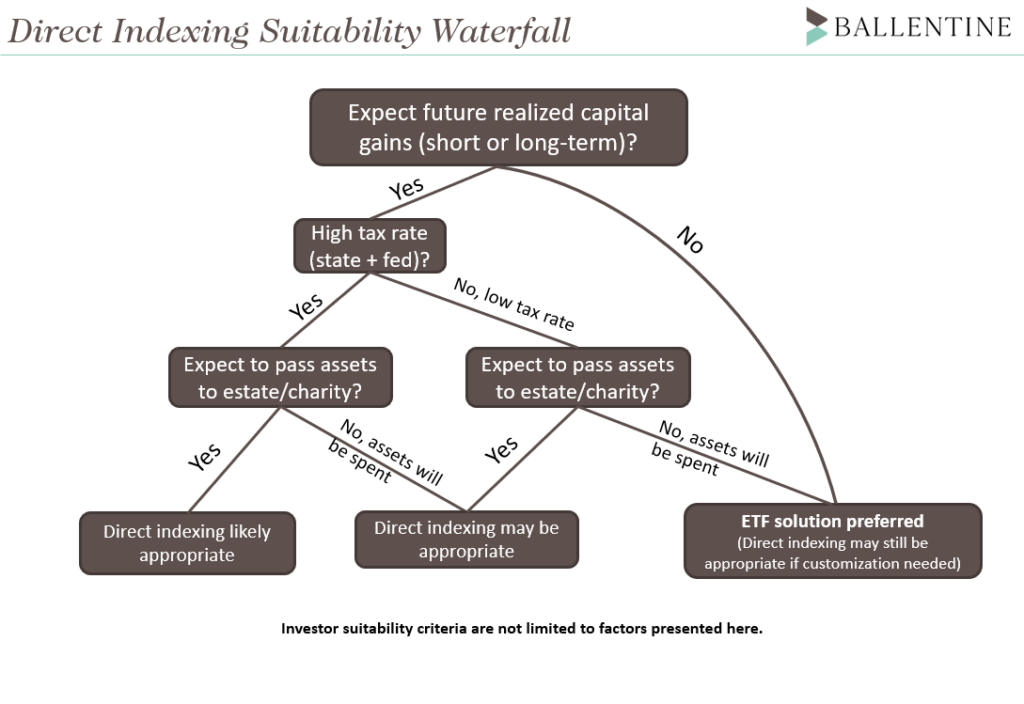

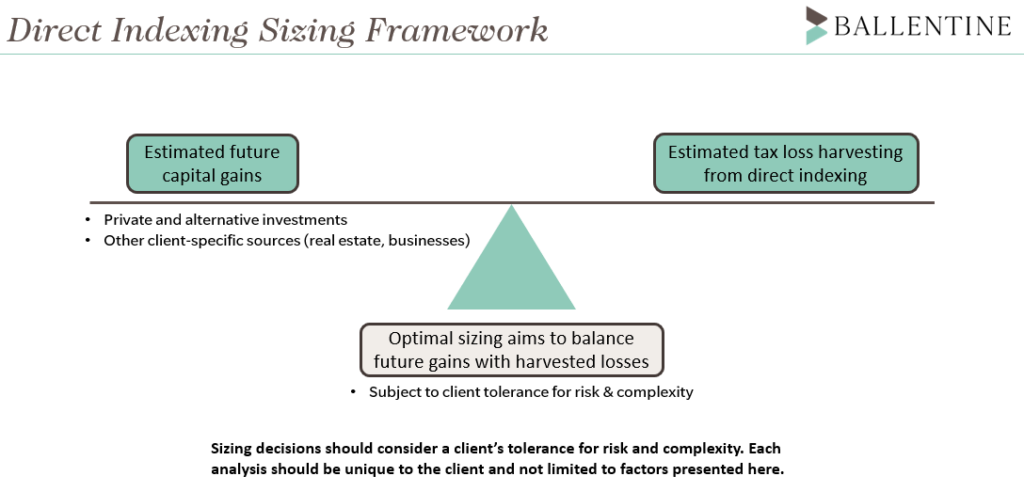

Sizing

The second “S” is sizing – how much tax loss harvesting is appropriate? Tax loss harvesting is wonderful – so long as the losses are utilized to offset capital gains within the investor’s lifetime. Otherwise, they are wasted. Direct indexing accounts should be sized with the goal of harvesting just enough losses to offset expected future capital gains. Anything beyond that is unnecessary.

To guide our sizing approach, we estimate both the investor’s future capital gains and loss harvesting from direct indexing, then aim to balance the two. Making these estimates is a necessary, but admittedly imprecise science – both can vary significantly based on market conditions and other factors.

Portfolio strategy and asset allocation form the starting points for estimating future capital gains. More specifically, allocations to private and alternative investments. Privates and alternatives exploit inefficiencies and illiquidity to attempt to generate returns above those available in public markets. But they also tend to be less tax efficient as they distribute all capital gains and income to investors. (In theory, public equities can be held forever or donated to charity, thus entirely avoiding capital gains taxes). These gains combined with other sources specific to the client form the target which we aim to offset via direct indexing.

Next, we turn to direct indexing. Using historical data and the investor’s specific strategy, we estimate the loss harvesting generated by a direct indexing account. Strategy decisions factor into these estimates – more on those later.

With estimates of both loss harvesting and future capital gains, we balance the equation. Let’s walk through a hypothetical example. Imagine a direct indexing account that is expected to generate roughly 5% of the account value in annual tax loss harvesting over 5-10 years. For future capital gains let us assume the investor allocates 25% of their portfolio to alternatives and private investments which we expect to return 10% per annum, all of which is comprised of realized capital gains. That produces 2.5% of the portfolio value in annual realized gains. Sizing the direct indexing account at 50% of the portfolio will achieve that goal (5% loss harvesting on half the portfolio equates to 2.5% of expected losses).

Some additional client-specific filters are needed, of course. Risk tolerance, portfolio capacity for direct indexing, or uncertainty around our estimates can all argue for a smaller sizing. With that in mind, our framework should be viewed as a starting point to be informed by the client’s overall financial situation and other qualitative factors.

Swapping

The third “S” in our framework is swapping. As a reminder, direct indexing strategies “unwrap” an ETF into a collection of individual stocks. This decomposition enables asset swapping or shifting assets between account types.

A basic swapping technique is gifting highly appreciated individual stocks to charities in lieu of cash. Imagine you’re getting ready to make an annual charitable gift to your alma mater or a favored charity. Instead of a cash contribution, you cherry-pick the most highly appreciated stock (or collection of stocks) in the portfolio and give that away instead. Two goals are accomplished: first, embedded gains in the portfolio are reduced. Second, cash that would have otherwise been gifted can instead be added to the direct indexing account, refreshing its cost basis and boosting tax loss harvesting.

A more sophisticated example has to do with estate and trust planning. Imagine locating a direct indexing account within a grantor trust with powers of substitution. The grantor receives the ongoing tax benefits from loss harvesting which occurs within the trust. But as the component holdings of the account become highly appreciated (again within the trust), they can be swapped back to the grantor’s estate and substituted with other assets, resetting cost basis within the trust. The appreciated holdings are then back within the investor’s estate and are eligible for a step-up in cost basis at their death. These techniques are advanced and require a full understanding of the client’s estate plan and financial picture. They may not be appropriate for many investors.

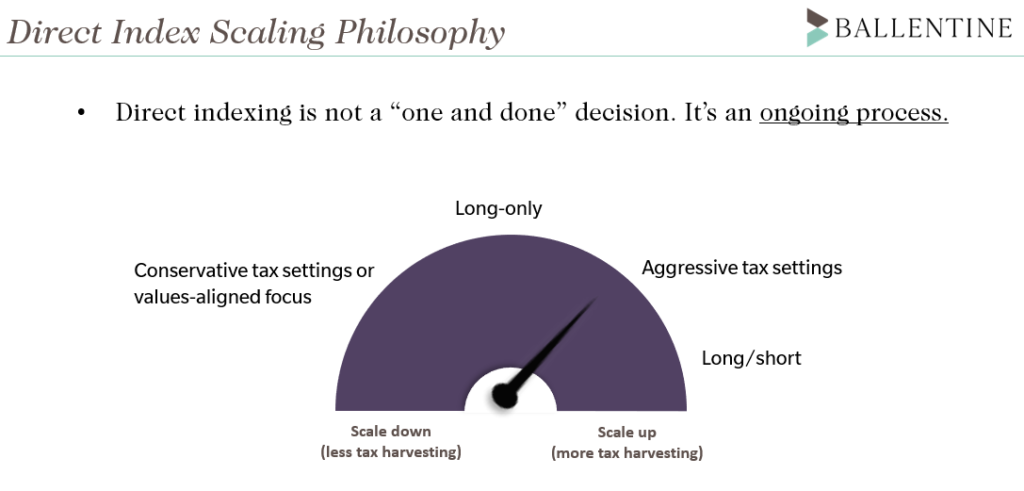

Scaling

The final “S” is Scaling, meaning varying the amount of tax loss harvesting through time. Imagine a situation where you anticipate a large private equity distribution or the sale of a business; tax-loss harvesting can be proactively “scaled” up to help reduce the tax burden (how? Adding more cash, tightening tracking error)Alternatively, an investor entering retirement may reasonably expect to fall into a lower tax bracket and pursue a “scaled” down approach.

A particularly potent scaling option can be found in “long/short” direct indexing. These are advanced strategies that employ leverage to add additional “long” stock exposure offset by “short” sales (bets against other stocks). This provides more tax loss harvesting opportunities without taking on additional net exposure to the market. And since markets tend to go up over time, bets against stocks via short sales produce consistent and sustainable tax losses. The tradeoff is higher implementation costs, tracking errors, complexity, and risks associated with leverage. However, the tax loss harvesting opportunity is substantial. This advanced scaling technique can be particularly useful in response to large, unexpected capital gains.

Conclusion

When it comes to public equity investment strategies we see two attractive options. One is simple but effective in almost any situation – low-cost exchange-traded funds. The other – direct indexing – is complex and requires a thoughtful framework to effectively implement. But when done correctly it offers a substantial benefit over ETFs for some taxable investors. We have developed this “4S” framework to inform our analysis of direct indexing for our clients. The factors detailed in this piece are not exhaustive – other qualitative inputs can move the needle. We hope this framework helps potential users of direct indexing to sift through the Wall Street marketing hype to determine if these strategies make sense for them.

[1] See performance data in our foundation piece on direct indexing: “The Next Frontier of Tax-Efficient Investing”

Read the PDF of this article here.

About Andrew Hacker, CFA, Research Manager

Andrew is a Research Manager at the firm and is responsible for research coverage of global equity markets. He is responsible for portfolio construction and manager selection for publicly traded equities and digital assets. His research also contributes to our overall market outlook.

The opportunity to offset capital gains with losses is limited by the tax codes of some states. For example, some states do not allow capital losses to be carried forward into the next tax year. Please consult your tax advisor for information about the application of this strategy in your state of tax residence. Any individual account’s ability to capitalize on component security losses may vary significantly based on account’s age, strategy, and other factors. While direct indexing may offer more opportunities to generate losses when compared to an ETF or mutual fund, the size and scope of the opportunities may vary. Ballentine Partners, LLC does not serve as an attorney, accountant, or insurance agent.

This report is the confidential work product of Ballentine Partners. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.

Please advise us if you have not been receiving account statements (at least quarterly) from the account custodian.